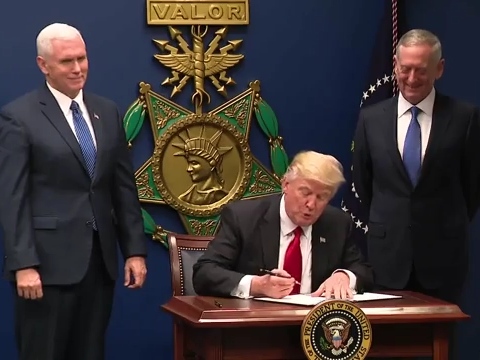

The Trump administration’s January 27th executive order banning refugees and certain legal immigrants from entering the United States galvanized businesses into action. Companies immediately affected by the ban, like airlines, scrambled to manage the impact on their customers. U.S.-based companies with global operations and diverse workforces, like Coca-Cola, Ford, Goldman Sachs, Google and Nike made forceful public statements opposing the ban. Technology and media companies expressed concern for their employees and operations. Starbucks announced plans to hire 10,000 refugees. Companies like Amazon and Microsoft joined the State of Washington’s successful lawsuit challenging the legality of the immigration ban. Apple and more than 125 other companies signed a brief defending the nationwide restraining order. Even companies that have not addressed the impact of the ban publicly are managing its fallout. From assisting affected employees to fielding inquiries from concerned employees and others, few large enterprises could avoid addressing the federal government’s sudden attempt to close U.S. borders to certain groups of people, targeting refugees and Muslims.

The Trump administration’s January 27th executive order banning refugees and certain legal immigrants from entering the United States galvanized businesses into action. Companies immediately affected by the ban, like airlines, scrambled to manage the impact on their customers. U.S.-based companies with global operations and diverse workforces, like Coca-Cola, Ford, Goldman Sachs, Google and Nike made forceful public statements opposing the ban. Technology and media companies expressed concern for their employees and operations. Starbucks announced plans to hire 10,000 refugees. Companies like Amazon and Microsoft joined the State of Washington’s successful lawsuit challenging the legality of the immigration ban. Apple and more than 125 other companies signed a brief defending the nationwide restraining order. Even companies that have not addressed the impact of the ban publicly are managing its fallout. From assisting affected employees to fielding inquiries from concerned employees and others, few large enterprises could avoid addressing the federal government’s sudden attempt to close U.S. borders to certain groups of people, targeting refugees and Muslims.

The immigration ban is the first of many ethical dilemmas companies will confront under this administration.

The Trump administration brings unprecedented levels of uncertainty for businesses. The immigration ban is the first of many ethical dilemmas companies will confront under this administration. Trump’s controversial proposals include detaining and deporting all undocumented residents of the United States, including children; and creating a Muslim registry. Corporate boards, CEOs and their advisors are asking themselves how the most extreme Trump proposals would affect their company’s people, customers and communities, and how their company should respond. Companies prefer not to address these questions on the fly.

The Trump administration brings unprecedented levels of uncertainty for businesses. The immigration ban is the first of many ethical dilemmas companies will confront under this administration. Trump’s controversial proposals include detaining and deporting all undocumented residents of the United States, including children; and creating a Muslim registry. Corporate boards, CEOs and their advisors are asking themselves how the most extreme Trump proposals would affect their company’s people, customers and communities, and how their company should respond. Companies prefer not to address these questions on the fly.

Well-managed companies anticipate risks to their business and plan accordingly. It is no surpsrise that some of the global brands moving quickly to defend the rights of their employees, customers and communities against harmful executive action on immigration in the United States have been working for years to integrate human rights considerations into their global operations. Nike, Starbucks, Coca-Cola, Google, Ford and Microsoft have all faced human rights challenges in the past – from child labor to complicity with abusive security forces to government censorship – and have drawn management lessons from their mistakes. Companies reacting to the immigration ban are pursuing many strategies used by companies seeking to meet their human rights responsibilities, but without articulating any conceptual framework for their actions.

The business and human rights movement provides a roadmap for managing business risks under Trump. Executives and managers looking for a conceptual framework to organize their responses to Trump’s policies, and road-tested tools to manage them, can apply the corporate responsibility to respect human rights to their United States operations.

The Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights

The business and human rights movement provides a roadmap for managing business risks under Trump.

“Business and human rights” is a management discipline that has emerged over the past three decades. An international benchmark, the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (2011) (PDF), reflects the working consensus among business, governments and civil society on what companies can do to meet their corporate responsibility to respect human rights. Specifically, companies must:

“Business and human rights” is a management discipline that has emerged over the past three decades. An international benchmark, the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (2011) (PDF), reflects the working consensus among business, governments and civil society on what companies can do to meet their corporate responsibility to respect human rights. Specifically, companies must:

- Avoid causing or contributing to adverse human rights impacts through their own activities, and address such impacts when they occur; and

- Seek to prevent or mitigate adverse human rights impacts that are directly linked to their operations, products or services by their business relationships, even if they have not contributed to those impacts.

To meet this standard, companies have adopted human rights policies, are conducting due diligence to understand the human rights impacts of their operations and business relationships, and finding ways to prevent, mitigate and remedy adverse human rights impacts.

Most attention has focused on the human rights impacts of multinationals outside their home countries, typically in places where corporate activity is connected to human rights violations – like child labor, human trafficking and torture – and where legal accountability for perpetrators and remedies for victims are lacking. The most familiar examples are sweatshops in global apparel supply chains and complicity with abusive security forces by oil and mining companies, but advocates have shined a spotlight on the human rights impacts of companies in sectors ranging from agriculture and consumer products to healthcare and technology.

Most attention has focused on the human rights impacts of multinationals outside their home countries, typically in places where corporate activity is connected to human rights violations – like child labor, human trafficking and torture – and where legal accountability for perpetrators and remedies for victims are lacking. The most familiar examples are sweatshops in global apparel supply chains and complicity with abusive security forces by oil and mining companies, but advocates have shined a spotlight on the human rights impacts of companies in sectors ranging from agriculture and consumer products to healthcare and technology.

Business and Human Rights under Trump

The business and human rights landscape in the United States shifted dramatically with the election of Donald Trump.

The business and human rights landscape in the United States shifted dramatically with the election of Donald Trump.

The business and human rights landscape in the United States shifted dramatically with the election of Donald Trump.

The prospect of stronger U.S. government action to protect individuals from corporate misconduct has vanished. One of the final initiatives of the Obama administration in December 2016 was the release of a U.S. National Action Plan on Responsible Business Conduct describing the federal policies and governmental expectations for the conduct of U.S corporations operating abroad, including their responsibility to respect human rights consistent with the UN Guiding Principles. Corporate accountability advocates are rightly concerned that the Trump administration will fail to consistently implement the laws and policies contained in the National Action Plan. The ideology and policy prescriptions of Trump’s advisors and cabinet, abetted by Republicans in Congress, means the likely weakening of protections for consumers, workers, and communities against corporate abuses under federal U.S. law, especially concerning the activities of U.S. companies abroad. Regulations of corporate conduct are more likely to be stripped than strengthened. (One exception may be the issue of tax avoidance, for which companies could face greater scrutiny if Trump’s rhetoric becomes policy.) The modest federal human rights reporting requirements enacted during the past decade, like the conflict mineral provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act, are already targeted for elimination. The Trump regime may even stop prosecuting companies for bribing foreign officials under the Foreign Corrupt Practice Act. Advocates will have to rely on other tools to promote corporate responsibility for human rights impacts.

Absent government enforcement, voluntary corporate action has become the backstop for meeting the corporate responsibility to respect human rights in the United States. The policy shift in Washington may be good news for business executives who subscribe to a “profits at all costs” business model. It is deeply troubling, however, for the business leaders, managers and employees who know that business success in the long run (beyond the next earnings cycle) is inextricably tied to meeting the expectations of customers, investors and employees that companies demonstrate corporate responsibility, their so-called “license to operate.” Leading companies, especially those companies that have integrated compliance and human rights standards into the way they do business, are unlikely to make bribery or human rights violations part of their business plans. Unethical executives will be less likely to get caught, but responsible companies will continue to comply with the spirit of the UN Guiding Principles. U.S. federal regulators may be instructed to look the other way when companies do harm, but the corporate responsibility spotlight now shines brighter than ever on business operations in the United States.

Absent government enforcement, voluntary corporate action has become the backstop for meeting the corporate responsibility to respect human rights in the United States. The policy shift in Washington may be good news for business executives who subscribe to a “profits at all costs” business model. It is deeply troubling, however, for the business leaders, managers and employees who know that business success in the long run (beyond the next earnings cycle) is inextricably tied to meeting the expectations of customers, investors and employees that companies demonstrate corporate responsibility, their so-called “license to operate.” Leading companies, especially those companies that have integrated compliance and human rights standards into the way they do business, are unlikely to make bribery or human rights violations part of their business plans. Unethical executives will be less likely to get caught, but responsible companies will continue to comply with the spirit of the UN Guiding Principles. U.S. federal regulators may be instructed to look the other way when companies do harm, but the corporate responsibility spotlight now shines brighter than ever on business operations in the United States.

In a complete role reversal, business leaders may need to mobilize to hold the U.S. government accountable for protecting human rights and obeying the Constitution. U.S. companies face the real prospect of human rights violations connected to their operations much closer to home. Multinationals operating in the United States will be asked to demonstrate that they are respecting human rights whenever U.S. government policies fall short of international standards, and significantly, if government actions violate the United States Constitution. Businesses will also face pressure, as they are right now regarding the immigration ban, to deploy corporate resources as a check on the U.S. government.

Rights under Threat

The corporate responsibility spotlight now shines brighter than ever on business operations in the United States.

Internationally recognized human rights threatened by proposed actions of the Trump administration include the rights to non-discrimination; to recognition and equality before the law; to protection from arbitrary arrest and from interference with privacy; to personal security; to freedom of opinion and expression; to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; to political participation; and to freedom of association. These rights, defined under international law in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and international human rights and labor treaties, are the focus of corporate efforts to manage their human rights impacts outside the United States. Other rights that have received less attention by most companies may now come into play, such as prohibitions of “propaganda for war” and “advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence” (ICCPR, Article 20), and the right of “ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities” to “enjoy their own culture, to profess and practice their own religions, or to use their own language.” (ICCPR, Article 27). The Trump campaign and administration have demonstrated a willingness to engage in such tactics in the United States, and to target minorities.

Internationally recognized human rights threatened by proposed actions of the Trump administration include the rights to non-discrimination; to recognition and equality before the law; to protection from arbitrary arrest and from interference with privacy; to personal security; to freedom of opinion and expression; to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; to political participation; and to freedom of association. These rights, defined under international law in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and international human rights and labor treaties, are the focus of corporate efforts to manage their human rights impacts outside the United States. Other rights that have received less attention by most companies may now come into play, such as prohibitions of “propaganda for war” and “advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence” (ICCPR, Article 20), and the right of “ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities” to “enjoy their own culture, to profess and practice their own religions, or to use their own language.” (ICCPR, Article 27). The Trump campaign and administration have demonstrated a willingness to engage in such tactics in the United States, and to target minorities.

The Corporate Responsibility to Respect the U.S. Constitution

Companies operating in the United States should consider the U.S. Constitution together with the international human rights instruments to define their potential human rights impacts. Most internationally recognized human rights are protected in some form under United States law at the federal, state and/or local level. The United States Constitution’s Bill of Rights, for example, enumerates rights including the free exercise of religion (First Amendment): the freedoms of speech, of the press, and of assembly (First Amendment); freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures (Fourth Amendment); the right to vote (Fifteenth, Nineteenth, Twenty-Fourth, Twenty-Sixth Amendments); and the rights to citizenship, due process and equal protection of the law (Fourteenth Amendment).

Companies operating in the United States should consider the U.S. Constitution together with the international human rights instruments to define their potential human rights impacts. Most internationally recognized human rights are protected in some form under United States law at the federal, state and/or local level. The United States Constitution’s Bill of Rights, for example, enumerates rights including the free exercise of religion (First Amendment): the freedoms of speech, of the press, and of assembly (First Amendment); freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures (Fourth Amendment); the right to vote (Fifteenth, Nineteenth, Twenty-Fourth, Twenty-Sixth Amendments); and the rights to citizenship, due process and equal protection of the law (Fourteenth Amendment).

Companies can add “US Constitutional rights” to human rights principles as another lens through which they manage the impacts of their operations in the United States.

Companies can add “US Constitutional rights” to human rights principles as another lens through which they manage the impacts of their operations in the United States. If federal, state or local authorities in the United States engage in systematic discrimination; target individuals or groups for harassment based on national origin or religion; curtail press freedoms; seek to arrest undocumented individuals; separate children from their families; or arbitrarily restrict the right to vote; their actions or omissions are likely to be both unconstitutional and violate international human rights.

Human Rights Impact Management

In the Trump era, companies must exercise due diligence to identify, prevent and mitigate the domestic human rights impacts of their operations and business relationships in the United States.

Companies can manage the risks of contributing or being connected to government actions that violate human and Constitutional rights using the same concepts and tools that apply a human rights lens to their non-U.S. operations. In the Trump era, companies must exercise due diligence to identify, prevent and mitigate the domestic human rights impacts of their operations and business relationships in the United States.

Companies can manage the risks of contributing or being connected to government actions that violate human and Constitutional rights using the same concepts and tools that apply a human rights lens to their non-U.S. operations. In the Trump era, companies must exercise due diligence to identify, prevent and mitigate the domestic human rights impacts of their operations and business relationships in the United States.

If U.S. government action violates rights, companies must take steps not to cause or contribute to any of the human rights impacts, and must be prepared to respond appropriately when any of these scenarios touch their people, products, or partners.

Companies should be prepared to do five things to manage their human rights impacts and meet their responsibilities to respect rights under Trump:

1. Protect employees.

When government actions threaten or harm employees, companies must act to support and protect them. The priority for companies in the wake of the immigration ban has been to identify affected employees, ensure their safety, and provide assistance, such as travel, legal and financial support. Providing employees with clear, accurate information about the immigration ban and its impact, so that individuals can take action to protect themselves and their families, is a first step companies can take to meet their responsibility to employees. Employees are the stakeholder group companies can help most directly, but businesses must also consider how to support and protect others connected to their particular business, such as customers, business partners and the communities where they operate.

When government actions threaten or harm employees, companies must act to support and protect them. The priority for companies in the wake of the immigration ban has been to identify affected employees, ensure their safety, and provide assistance, such as travel, legal and financial support. Providing employees with clear, accurate information about the immigration ban and its impact, so that individuals can take action to protect themselves and their families, is a first step companies can take to meet their responsibility to employees. Employees are the stakeholder group companies can help most directly, but businesses must also consider how to support and protect others connected to their particular business, such as customers, business partners and the communities where they operate.

2. Avoid complicity.

Companies must ensure that they are not contributing to rights violations in any way. A practical first step for businesses is to apply international standards for effective human rights due diligence, such as human rights impact assessments, to their corporate operations and business relationships in the United States. Airlines that refuse to allow passage to refugees in the wake of the immigration ban, for example, are at risk of complicity with violations of the right to seek asylum under international law. Particularly important will be corporate relationships with the U.S. government, its agencies and the Trump administration. CEOs serving as advisors to the Trump administration are already attracting extra scrutiny from customers and rights advocates. If the Trump administration were to attempt to detain all undocumented residents of the United Sates or to create a national registry based on religious belief, companies should not provide information nor supply products or services that would foreseeably contribute to rights violations.

Companies must ensure that they are not contributing to rights violations in any way. A practical first step for businesses is to apply international standards for effective human rights due diligence, such as human rights impact assessments, to their corporate operations and business relationships in the United States. Airlines that refuse to allow passage to refugees in the wake of the immigration ban, for example, are at risk of complicity with violations of the right to seek asylum under international law. Particularly important will be corporate relationships with the U.S. government, its agencies and the Trump administration. CEOs serving as advisors to the Trump administration are already attracting extra scrutiny from customers and rights advocates. If the Trump administration were to attempt to detain all undocumented residents of the United Sates or to create a national registry based on religious belief, companies should not provide information nor supply products or services that would foreseeably contribute to rights violations.

Once a company understands how its operations, products or relationships are connected to potential or actual rights violations in the United States, the business must act to cease or prevent its own violation or contribution, and use its leverage to prevent and mitigate violations by others. Exercising leverage may take the form of challenging rights violations or opposing harmful policies. Companies connected to human rights violations committed by government security forces outside the United States have intervened with government authorities seeking to prevent the violations, promoted standard-setting and training initiatives to prevent future violations, and have ended business relationships to ensure they are not connected to violations. U.S. companies are beginning to use their leverage, individually and collectively, to prevent and mitigate the impact of the immigration ban. One can imagine scenarios in which companies refuse to provide goods or services to U.S. government agencies violating rights, or in the case of non-U.S. companies, pull out of the U.S. market altogether if the violations are sufficiently severe.

3. Mitigate harmful impacts.

When companies are unable to stop harmful policies and actions by others, they can seek to mitigate the negative impact on their employees, customers, business partners and communities. Companies have sought to comply with the spirit of international human rights standards outside the United States by protecting rights “within the factory walls.” Brands sourcing from factories in China, for example, where independent trade unions are banned, have promoted the creation of factory worker councils to bring concerns over working conditions to management. Businesses must consider ways to ensure that their U.S. workplaces provide safe spaces where individual rights are protected. Adopting workplace policies reinforcing a commitment to non-discrimination and prohibiting the harassment of any individual based on national origin or immigration status is one concrete way to meet the corporate responsibility to respect rights.

When companies are unable to stop harmful policies and actions by others, they can seek to mitigate the negative impact on their employees, customers, business partners and communities. Companies have sought to comply with the spirit of international human rights standards outside the United States by protecting rights “within the factory walls.” Brands sourcing from factories in China, for example, where independent trade unions are banned, have promoted the creation of factory worker councils to bring concerns over working conditions to management. Businesses must consider ways to ensure that their U.S. workplaces provide safe spaces where individual rights are protected. Adopting workplace policies reinforcing a commitment to non-discrimination and prohibiting the harassment of any individual based on national origin or immigration status is one concrete way to meet the corporate responsibility to respect rights.

4. Challenge rights violations.

Companies must obey the laws wherever they operate, yet the corporate responsibility to respect human rights goes beyond legal compliance. What is lawful may still violate an individual’s rights. Challenges arise for companies when local law or its enforcement conflicts with international standards. Companies must be prepared to challenge government actions that are unconstitutional or violate human rights.

In countries where laws explicitly contradict international human rights standards, companies have found ways to minimize their connection to human rights violations by others. In China, Brazil and elsewhere, for example, foreign technology firms have insisted upon valid judicial orders before acquiescing to demands from government officials to turn over personally identifiable user information for questionable purposes. Companies may face similar situations in the United States if asked by law enforcement authorities to turn over personal information related to their employees’ or customers’ national origin, immigration status or religious beliefs. Businesses can exhaust all available legal processes, as Apple successfully refused to collaborate with the FBI to unlock encrypted iPhones, and challenge the legality of government actions in court, as some companies are now doing in opposition to the immigration ban. Companies can also communicate publicly about government actions that violate rights, using transparency to highlight actual and potential rights violations. Since 2009, for example, Google has published a “Transparency Report” with data on government requests to hand over user data, and how the company responds. Companies will need to be more transparent about what the U.S. government under Trump asks them to do, and the likely consequences of compliance.

In countries where laws explicitly contradict international human rights standards, companies have found ways to minimize their connection to human rights violations by others. In China, Brazil and elsewhere, for example, foreign technology firms have insisted upon valid judicial orders before acquiescing to demands from government officials to turn over personally identifiable user information for questionable purposes. Companies may face similar situations in the United States if asked by law enforcement authorities to turn over personal information related to their employees’ or customers’ national origin, immigration status or religious beliefs. Businesses can exhaust all available legal processes, as Apple successfully refused to collaborate with the FBI to unlock encrypted iPhones, and challenge the legality of government actions in court, as some companies are now doing in opposition to the immigration ban. Companies can also communicate publicly about government actions that violate rights, using transparency to highlight actual and potential rights violations. Since 2009, for example, Google has published a “Transparency Report” with data on government requests to hand over user data, and how the company responds. Companies will need to be more transparent about what the U.S. government under Trump asks them to do, and the likely consequences of compliance.

5. Oppose harmful policies.

Companies in diverse sectors are speaking out against the immigration ban. In response to government actions targeting Muslims, immigrants and refugees, companies are directing corporate resources toward organizations defending these groups and their rights. Multinational companies have learned that the corporate responsibility to respect human rights often requires advocating for governments to fulfill their own human rights obligations. Companies have criticized rights violations by governments around the world and opposed harmful government policies privately, publicly and in partnership with others through business associations, coalitions and advocacy networks. More businesses will need to become public rights advocates in the United States.

Companies in diverse sectors are speaking out against the immigration ban. In response to government actions targeting Muslims, immigrants and refugees, companies are directing corporate resources toward organizations defending these groups and their rights. Multinational companies have learned that the corporate responsibility to respect human rights often requires advocating for governments to fulfill their own human rights obligations. Companies have criticized rights violations by governments around the world and opposed harmful government policies privately, publicly and in partnership with others through business associations, coalitions and advocacy networks. More businesses will need to become public rights advocates in the United States.

Corporate advocacy is most effective when it reinforces company values. U.S. companies in recent years have publicly opposed state laws in the United States that would permit discrimination based on sexual preference. Since the election, U.S. companies have spoken out to let their stakeholders know where they stand on the most extreme Trump proposals.

Corporate advocacy is most effective when it reinforces company values. U.S. companies in recent years have publicly opposed state laws in the United States that would permit discrimination based on sexual preference. Since the election, U.S. companies have spoken out to let their stakeholders know where they stand on the most extreme Trump proposals.

When engaging in public advocacy on rights issues in the United States, companies will need to overcome any cultural reluctance to speak out publicly. This will seem even riskier because Trump has embraced the “naming and shaming” of individual companies to advance his political agenda. Companies at the center of the business and human rights movement, however, understand that customers, employees and investors often view corporate silence in the face of rights violations as tacit complicity.

Human rights impact management accounts for all of these strategies.

The discipline that accounts for all of these strategies is human rights impact management, an approach that more and more business leaders may now embrace to effectively manage the Trump administration. What is your company doing to meet its corporate responsibility to respect rights in the United States?

Anthony P. Ewing ([email protected]) is a Senior Advisor at Logos Consulting Group and a Lecturer at Columbia Law School, where he teaches business and human rights.

“

“

The business and human rights landscape in the United States shifted dramatically with the election of Donald Trump.

The business and human rights landscape in the United States shifted dramatically with the election of Donald Trump.

Internationally recognized human rights threatened by proposed actions of the Trump administration

Internationally recognized human rights threatened by proposed actions of the Trump administration  Companies operating in the United States should consider the U.S. Constitution together with the international human rights instruments to define their potential human rights impacts. Most internationally recognized human rights are protected in some form under United States law at the federal, state and/or local level. The United States Constitution’s Bill of Rights, for example, enumerates rights including the free exercise of religion (First Amendment): the freedoms of speech, of the press, and of assembly (First Amendment); freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures (Fourth Amendment); the right to vote (Fifteenth, Nineteenth, Twenty-Fourth, Twenty-Sixth Amendments); and the rights to citizenship, due process and equal protection of the law (Fourteenth Amendment).

Companies operating in the United States should consider the U.S. Constitution together with the international human rights instruments to define their potential human rights impacts. Most internationally recognized human rights are protected in some form under United States law at the federal, state and/or local level. The United States Constitution’s Bill of Rights, for example, enumerates rights including the free exercise of religion (First Amendment): the freedoms of speech, of the press, and of assembly (First Amendment); freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures (Fourth Amendment); the right to vote (Fifteenth, Nineteenth, Twenty-Fourth, Twenty-Sixth Amendments); and the rights to citizenship, due process and equal protection of the law (Fourteenth Amendment). Companies can manage the risks of contributing or being connected to government actions that violate human and Constitutional rights using the same concepts and tools that apply a human rights lens to their non-U.S. operations. In the Trump era, companies must exercise due diligence to identify, prevent and mitigate the domestic human rights impacts of their operations and business relationships in the United States.

Companies can manage the risks of contributing or being connected to government actions that violate human and Constitutional rights using the same concepts and tools that apply a human rights lens to their non-U.S. operations. In the Trump era, companies must exercise due diligence to identify, prevent and mitigate the domestic human rights impacts of their operations and business relationships in the United States. When government actions threaten or harm employees, companies must act to support and protect them. The priority for companies in the wake of the immigration ban has been to identify affected employees, ensure their safety, and provide assistance, such as travel, legal and financial support. Providing employees with clear, accurate information about the immigration ban and its impact, so that individuals can take action to protect themselves and their families, is a first step companies can take to meet their responsibility to employees. Employees are the stakeholder group companies can help most directly, but businesses must also consider how to support and protect others connected to their particular business, such as customers, business partners and the communities where they operate.

When government actions threaten or harm employees, companies must act to support and protect them. The priority for companies in the wake of the immigration ban has been to identify affected employees, ensure their safety, and provide assistance, such as travel, legal and financial support. Providing employees with clear, accurate information about the immigration ban and its impact, so that individuals can take action to protect themselves and their families, is a first step companies can take to meet their responsibility to employees. Employees are the stakeholder group companies can help most directly, but businesses must also consider how to support and protect others connected to their particular business, such as customers, business partners and the communities where they operate.

When companies are unable to stop harmful policies and actions by others, they can seek to mitigate the negative impact on their employees, customers, business partners and communities. Companies have sought to comply with the spirit of international human rights standards outside the United States by protecting rights “within the factory walls.” Brands sourcing from factories in China, for example, where independent trade unions are banned, have promoted the creation of factory worker councils to bring concerns over working conditions to management. Businesses must consider ways to ensure that their U.S. workplaces provide safe spaces where individual rights are protected. Adopting workplace policies reinforcing a commitment to non-discrimination and prohibiting the harassment of any individual based on national origin or immigration status is one concrete way to meet the corporate responsibility to respect rights.

When companies are unable to stop harmful policies and actions by others, they can seek to mitigate the negative impact on their employees, customers, business partners and communities. Companies have sought to comply with the spirit of international human rights standards outside the United States by protecting rights “within the factory walls.” Brands sourcing from factories in China, for example, where independent trade unions are banned, have promoted the creation of factory worker councils to bring concerns over working conditions to management. Businesses must consider ways to ensure that their U.S. workplaces provide safe spaces where individual rights are protected. Adopting workplace policies reinforcing a commitment to non-discrimination and prohibiting the harassment of any individual based on national origin or immigration status is one concrete way to meet the corporate responsibility to respect rights. In countries where laws explicitly contradict international human rights standards, companies have found ways to minimize their connection to human rights violations by others. In China, Brazil and elsewhere, for example, foreign technology firms have insisted upon valid judicial orders before acquiescing to demands from government officials to turn over personally identifiable user information for questionable purposes. Companies may face similar situations in the United States if asked by law enforcement authorities to turn over personal information related to their employees’ or customers’ national origin, immigration status or religious beliefs. Businesses can exhaust all available legal processes, as Apple successfully refused to collaborate with the FBI to unlock encrypted iPhones, and challenge the legality of government actions in court, as some companies are now doing in opposition to the immigration ban. Companies can also communicate publicly about government actions that violate rights, using transparency to highlight actual and potential rights violations. Since 2009, for example, Google has published a “

In countries where laws explicitly contradict international human rights standards, companies have found ways to minimize their connection to human rights violations by others. In China, Brazil and elsewhere, for example, foreign technology firms have insisted upon valid judicial orders before acquiescing to demands from government officials to turn over personally identifiable user information for questionable purposes. Companies may face similar situations in the United States if asked by law enforcement authorities to turn over personal information related to their employees’ or customers’ national origin, immigration status or religious beliefs. Businesses can exhaust all available legal processes, as Apple successfully refused to collaborate with the FBI to unlock encrypted iPhones, and challenge the legality of government actions in court, as some companies are now doing in opposition to the immigration ban. Companies can also communicate publicly about government actions that violate rights, using transparency to highlight actual and potential rights violations. Since 2009, for example, Google has published a “ Companies in diverse sectors are speaking out against the immigration ban. In response to government actions targeting Muslims, immigrants and refugees, companies are directing corporate resources toward organizations defending these groups and their rights. Multinational companies have learned that the corporate responsibility to respect human rights often requires advocating for governments to fulfill their own human rights obligations. Companies have criticized rights violations by governments around the world and opposed harmful government policies privately, publicly and in partnership with others through business associations, coalitions and advocacy networks. More businesses will need to become public rights advocates in the United States.

Companies in diverse sectors are speaking out against the immigration ban. In response to government actions targeting Muslims, immigrants and refugees, companies are directing corporate resources toward organizations defending these groups and their rights. Multinational companies have learned that the corporate responsibility to respect human rights often requires advocating for governments to fulfill their own human rights obligations. Companies have criticized rights violations by governments around the world and opposed harmful government policies privately, publicly and in partnership with others through business associations, coalitions and advocacy networks. More businesses will need to become public rights advocates in the United States.  Corporate advocacy is most effective when it reinforces company values. U.S. companies in recent years have publicly opposed state laws in the United States that would permit discrimination based on sexual preference. Since the election, U.S. companies have

Corporate advocacy is most effective when it reinforces company values. U.S. companies in recent years have publicly opposed state laws in the United States that would permit discrimination based on sexual preference. Since the election, U.S. companies have