Helio Fred Garcia | Bio | Posts

Helio Fred Garcia | Bio | Posts

29 Aug 2015

Ten years ago today Hurricane Katrina made landfall. The rest, as they say, is history.

I won’t recount that history day-by-day here. There are plenty of special reports on TV and in the newspapers this weekend that help us see the horror as it unfolded. For a day-by-day timeline of the federal response, see Chapter 3 of The Power of Communication, or see Failure of Initiative, the final report of the U.S. House of Representatives Select Bipartisan Committee to Investigate the Preparation for and Response to Hurricane Katrina. That congressional report concluded:

“The Select Committee identified failures at all levels of government that significantly undermined and detracted from the heroic efforts of first responders, private individuals and organizations, faith-based groups, and others.”

But on the tenth anniversary of the flood, we have the opportunity to learn from the mistakes of that bungled response and to re-commit to the discipline of effective crisis response. I will hit the high points (or low points) of Katrina response as teachable moments.

I monitored the hurricane and flood and then deployed to New Orleans in the second week as part of a corporate response to the disaster. I saw first hand the consequence of the government’s ineffective handling of the crisis.

The author documenting Katrina damage.

The federal government’s response to Katrina was bumbling, disorganized, and dishonest. It cost hundreds of lives. Many of the nearly 1,500 deaths in New Orleans happened in the days following the flood. Many of those were preventable.

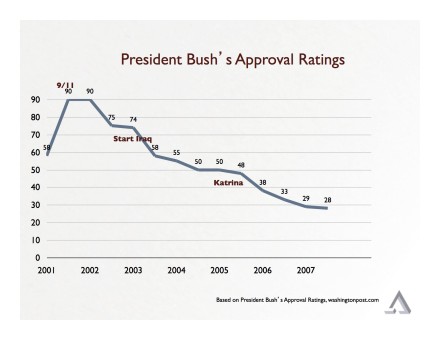

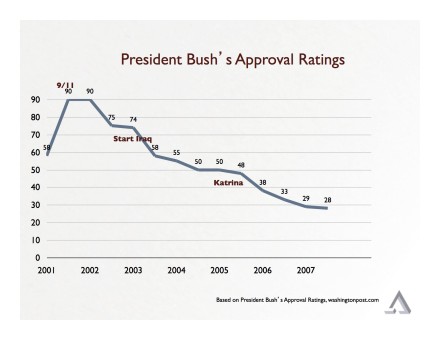

And the bungled response cost President George W. Bush his reputation. Until Katrina, President Bush had enjoyed a job approval rating above 50 percent. He had won re-election in a tough campaign just 10 months earlier. But after Katrina his job approval fell below 50 percent and never recovered. It fell first to 42 percent and a month later to 38 percent, and was below 30 percent the following year. President Bush finished his presidency with the lowest approval ratings of any president.

That loss of trust and reputation was preventable. Because most of the bungled response was preventable.

Effective Crisis Management is a Leadership Discipline

Crisis management is the management of choices – the management of decisions that leaders make when things have the potential to go very wrong.

Effective crisis management helps leaders and organizations make critical business decisions that can prevent, mitigate, or recover from an event that threatens trust, reputation, assets, operations, and competitive position.

There is a rigor to effective crisis management that is equivalent to the rigor found in other business processes. But that rigor is often unknown, ignored, or misapplied by many leaders, to their own and their organizations’ misfortune.

That rigor includes a systematic way to think in a crisis.

Many leaders who otherwise are gifted managers – managing finance, or engineering, or marketing, or any other professional discipline, or even a whole company or government – throw rigor to the wind when a crisis emerges. Then they either make up a response on the fly or try to cobble together bits of knowledge from other parts of their experience. Or they ignore the crisis until it is too late. Or they think that their problem is one of public relations that can be rationalized away.

All of these things happened in Katrina. Indeed, from the President to the Secretary of Homeland Security to the Director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, there was lack of situational awareness, ineffective and dishonest assurances of an imminent response, and then denial of their own mis-steps. They focused more on saying what sounded good, but were singularly unable to deliver on the assurances they made.

August 31, 2005 — Michael Chertoff, Secretary of Homeland Security, addresses the media. Photo by Ed Edahl/FEMA

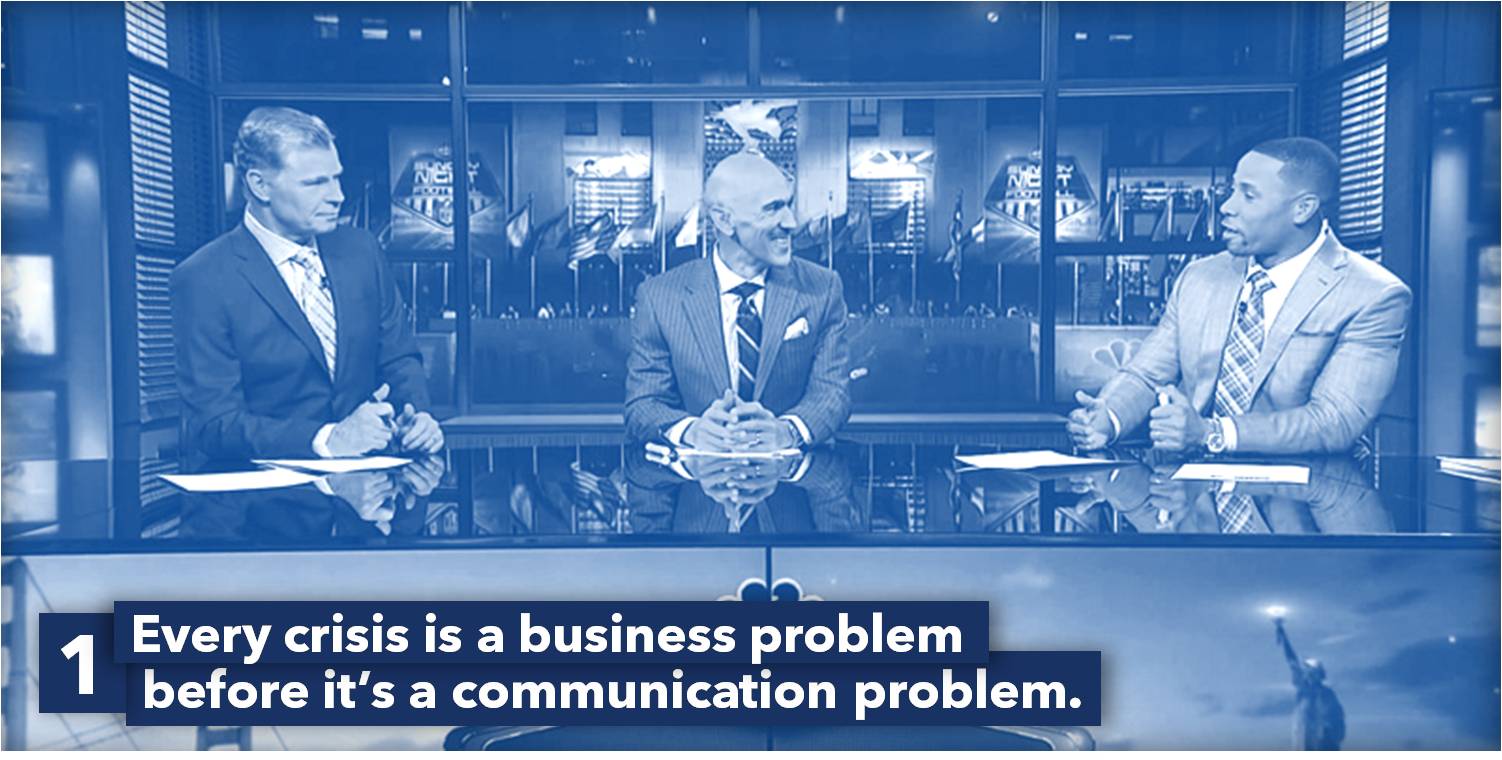

Every Crisis is a Business Problem Before it is a Communication Problem

Crisis management is far more than skillful public relations. Seeing PR as the solution to a crisis is a recipe for failure.

Every crisis is a business problem before it is a communication problem, and you cannot communicate your way out of a business problem.

The government set the bar very high early in the Katrina crisis.

The day before the hurricane made landfall President Bush went on television to reassure the citizens of New Orleans and the surrounding areas. He said,

“We will do everything in our power to help the people and the communities affected by the storm.”

FEMA Director Michael Brown also reassured the public:

“FEMA is not going to hesitate at all in this storm. We’re going to move fast, we’re going to move quick, we’re going to do whatever it takes to help disaster victims.”

FEMA chief Michael Brown alongside Louisiana Governor Kathleen Blanco, center, and U.S. Senator Mary Landrieu, left.

These were the right things to say.

But simply saying them was not enough.

Regrettably, both FEMA and the larger US government, having set those expectations, spent the next week dramatically under-delivering on them. As the horror that New Orleans experienced unfolded over the next few days, the government’s lack of effective action, and the disconnect between the rhetoric and the work, defined the president and his administration.

Crises play out in an environment of emotional resonance: fear, anxiety, anger, shame, embarrassment and other, often confused, emotions. Effective crisis communication, combined with effective management of other elements of a crisis, can address and even neutralize these emotional reactions.

New Orleans flooded on August 29, 2005

Crisis Response =

Effective Action + Effective Communication

Effective crisis response consists of a carefully managed process that calibrates smart actions with smart communication.

The key to making smart choices is to use the right decision criteria – the proper basis for choice. And that means asking the right questions.

Indeed, in my experience working on and studying thousands of crises over more than 35 years, the most effectively handled crises were the ones where leaders asked the right question. Ask the right question, and the solution can become clear within a matter of minutes. But asking the right question requires mental readiness; a readiness to shift perspective and to think differently.

The Leadership Discipline of Mental Readiness

Most counter-productive crisis responses begin with leaders asking some version of What should we do? Or What should we say? The challenge with this kind of question is that it focuses on the we – on the entity or leader in crisis. This results in the consideration of options that may make the people in midst of crisis feel good. But it is unlikely to lead to what is necessary to maintain trust, confidence, and support of those people whose trust, confidence, and support are critical to the organization.

What is needed is a different kind of thinking that begins not with the I/me/we/us but rather with the they/them – with the stakeholders who matter to the organization. The leadership discipline of mental readiness – the readiness to shift frames of reference from the first person — I/me/we/us — to the third person — they/them — makes all the difference.

And that’s because of the way trust works.

Maintaining Trust: Meet Expectations

A common goal for most organizations and leaders in crises is to maintain the trust and confidence of those who matter – shareholders, employees, customers, regulators, residents, citizens, voters, etc.

Trust arises when stakeholders’ legitimate expectations are met. Trust falls when expectations are unmet.

Asking What should we do? runs the serious risk of failing even to consider stakeholders’ expectations. Worse, it further risks the leader becoming stuck in his or her own perspective, in I/me/we/us. Hence, such crisis whoppers as BP CEO Tony Hayward’s “I’d like my life back,” or even President Richard Nixon’s “I am not a crook.”

Most crisis response failures can be traced back to the ultimate decision-makers focusing on their own frame of reference rather than on their stakeholders. This was the case in Katrina.

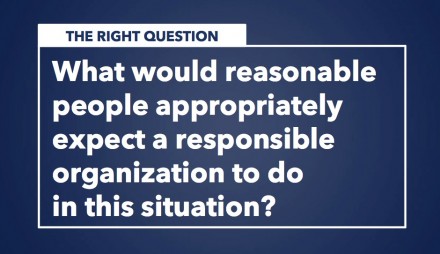

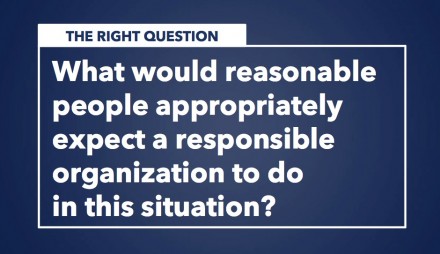

The right question to ask when determining the appropriate course of action in a crisis is not What should we do. Rather, it is this: What would reasonable people appropriately expect a responsible organization or leader to do when facing this kind of situation?

Framing decisions in light of stakeholder expectations leads to smarter choices faster, and maintains stakeholders’ trust.

For any stakeholder group we can answer the question, What would reasonable members of this stakeholder group appropriately expect a responsible organization or leader to do? to a very granular level. And at the very least, one way to determine stakeholder expectations is to reflect on the expectations we ourselves have set. So, in Katrina, President Bush set the expectation that the the federal government would do everything in its power to help the people affected by the storm. FEMA chief Michael Brown said that FEMA would not hesitate at all, but would move fast and do whatever it takes to help disaster victims.

But when FEMA was seen to be slow and to create obstacles to rapid response, and when the U.S. government was not seen to be responding or even acknowledging the gravity of the situation, trust began to fall simply because the expectations the government itself had set were not being fulfilled.

Photo by the author.

We can inventory expectations to a very granular level for each stakeholder group, and we can then work to fulfill those particular expectations.

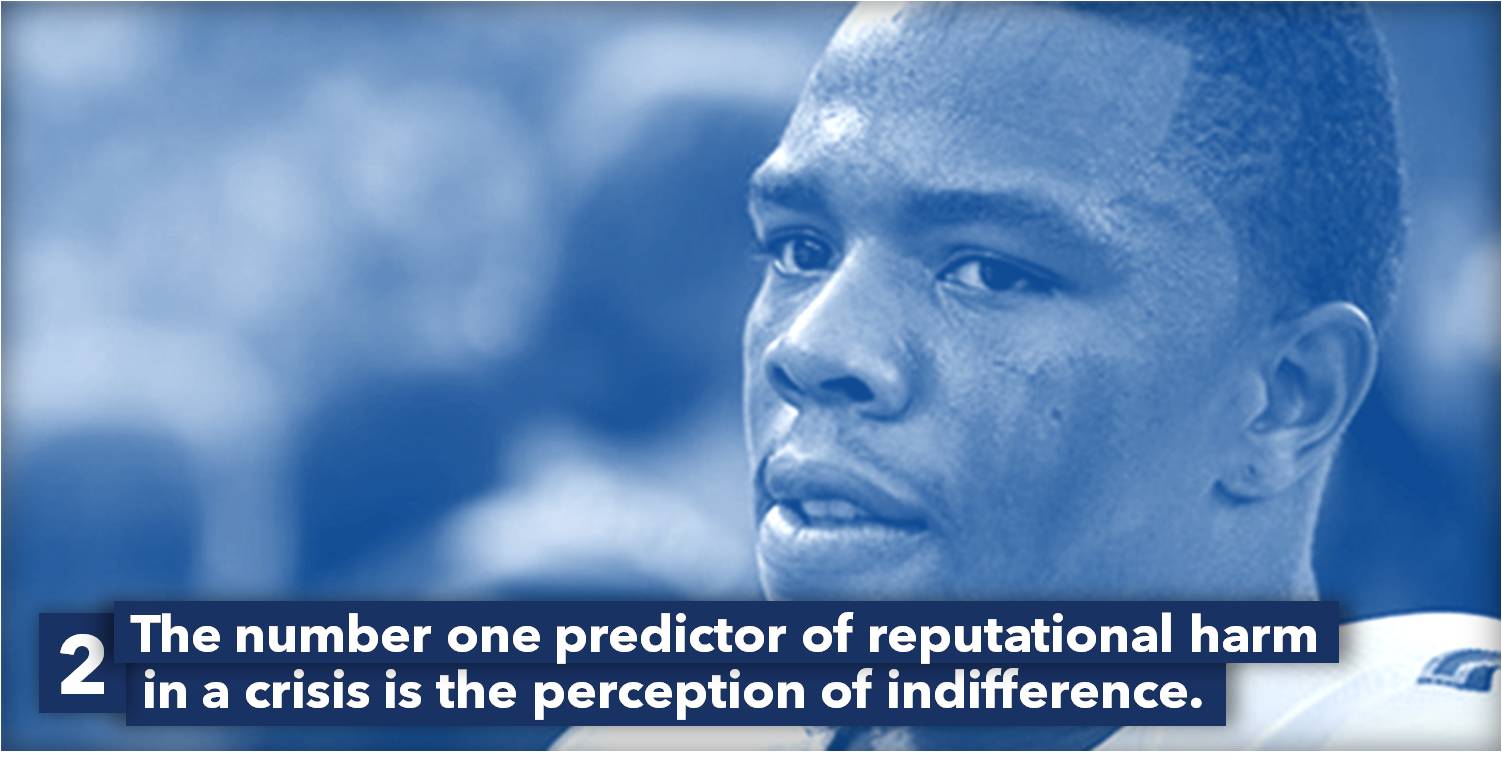

But regardless the particular expectations of any given stakeholder group, there is a common expectation that applies to all stakeholder groups all the time: In a crisis, all stakeholders expect a responsible organization or leader to care. To care that something has happened; to care that people need help; to care that something needs to be done.

One of the common patterns in crisis is this: The single biggest predictor of loss of trust and confidence, of loss of reputation, and of financial and operational harm, is the perception that the organization or leader do not care.

So effective crisis response, at a minimum, begins with a timely demonstration of caring. And it continues with a persistent demonstration that the organization and leader continue to care, for as long as the expectation of caring exists.

This is what was sorely lacking in the government’s response to Katrina. Officials said they cared; but the tangible demonstration of caring didn’t match the rhetoric.

New Orleans flooded on a Monday. Throughout that day and Tuesday, the government kept assuring the news media that FEMA and other agencies were on the ground and helping the victims. But news coverage showed little federal presence except for U.S. Coast Guard helicopter rescues. But no staging areas for victims; no shelters; but hundreds of people, mostly African-American, struggling against the rising waters and without help. On Tuesday the news media persistently questioned why there was little evidence of federal help for the city, noting even that dead bodies continued to float by.

On that Wednesday the media not only covered the lack of a FEMA presence on the ground, but also how FEMA prevented or stalled potential aid from other sources. For example, a fourteen-car caravan arranged by the sheriff of Loudoun County, Virginia, carrying supplies of water and food, was not allowed into the city. FEMA stopped tractor trailers carrying water to the supply staging area in Alexandria, Louisiana because they did not have the necessary paperwork. CNN also reported that during the weekend before the flood Mayor Nagin had made a call for firefighters to help with rescue operations. But as firefighters from across the country arrived to help victims, they were first sent by FEMA to Atlanta for a day long training program in community relations and sexual harassment. When they arrived in New Orleans, the volunteer firefighters were permitted only to give out flyers with FEMA number, but were forbidden from engaging in rescue operations. The media reported not only the resentment felt by the first responders, but also how FEMA’s policies hurt those people who were begging for aid in New Orleans.

That day Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff held a press conference in which he said,

“We are extremely pleased with every element of the federal government, all of our federal partners, have made to this terrible tragedy.”

That day Mayor Ray Nagin went on the radio and blasted the federal government for its failure to respond quickly:

“I don’t want to see anyone do any more g*d-dammed press conferences. Put a moratorium on press conferences. Don’t tell me forty thousand people are coming here. They’re not here!”

On Thursday, the news media reported that hundreds of people who had been sheltering at the New Orleans Convention Center without food, water, blankets, or any other help. FEMA Director Michael Brown went on four network news programs and admitted that FEMA had been unaware of the people at the convention center until the news media reported it.

That day commentators and late-night comedians began to question Mr. Brown’s fitness to serve.

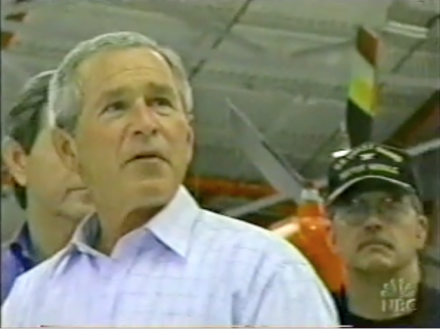

On Friday President Bush visited the area, and famously praised Mr. Brown, addressing him by his nickname:

“Brownie, you’re doing a heck of a job.”

President George W. Bush addressing FEMA Director Michael Brown: “Brownie, you’re doing a heck of a job.”

That caught people’s attention (and became a defining quote of the President Bush’s tenure as president). Media analysts wondered why the President would say that: Did he not know how incompetent Brown seemed to many people? Did he know and not care? Or did he actually want the ineffective response? It showed a president out of touch, or worse. This meme began to make its way across the television networks.

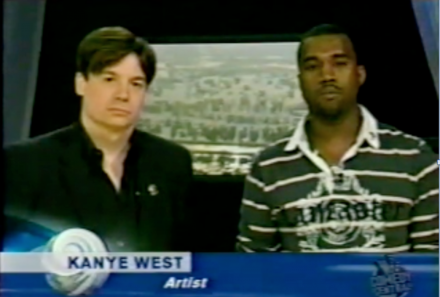

That night, Friday, on a live televised concert to raise funds for Katrina victims, entertainer Kanye West gave voice to the pent up frustrations of many:

“George Bush doesn’t care about black people.”

Kanye West gave voice to pent-up frustrations when he declared on live TV: “George Bush doesn’t care about black people.”

This changed the dynamic completely. The next morning, six days after the flood, the President spoke to the media in front of the White House. Flanked by Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, Joint Chiefs Chairman Richard Meyers, and Homeland Security Secretary Chertoff, the president acknowledged shortfalls in the federal response and committed to direct a more effective response. He said,

“Many of our citizens are simply not getting the help they need, especially in New Orleans. And that is unacceptable.”

After six days of seeming out of touch, the acknowledgement of the inadequate response seemed a heartening development. That day a larger federal presence was seen in New Orleans and President Bush ordered over 7,000 troops and an additional 10,000 National Guardsmen to the disaster area.

On the weekend talk shows, the focus shifted from why the response was inadequate to who was to blame for it.

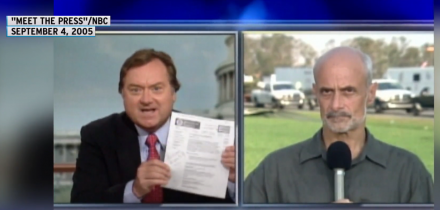

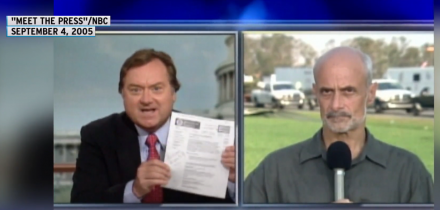

Meet The Press host Tim Russert with Homeland Security Secretary Chertoff

Homeland Security Secretary Chertoff appeared on NBC’s Meet The Press and was questioned by host Tim Russert. Russert asked whether Chertoff or anyone who reported to him would resign given the poor response. He quoted the Republican senator from Louisiana, David Vitter, who gave Secretary Chertoff a grade of F. He noted that Mitt Romney, Republican governor of Massachusetts, said that the U.S. is now an embarrassment to the world. He then challenged Secretary Chertoff:

“Your website says that your department assumes primary responsibility for a natural disaster. If you knew that a Hurricane Three storm was coming, why weren’t buses, trains, planes, cruise ships, trucks provided on Friday, Saturday, Sunday to evacuate people before the storm?”

Secretary Chertoff gave a response that was, at best, disingenuous. He said,

“Tim, the way that emergency operations act under the law is – the responsibility, the power, the authority to order an evacuation rests with state and local officials.”

Even if the statement were true, it was a sharp contrast from President Bush’s and FEMA Director Brown’s assurances that the federal government would do everything it could to help those affected by the storm. But as a PBS Frontline special pointed out, evacuation is a shared responsibility. The law establishing FEMA spells out:

“The functions of the Federal Emergency Management Agency include…conducting emergency operations to save lives and property through positioning emergency equipment and supplies, through evacuating potential victims, through providing food, water, shelter, and medical care to those in need, and through restoring critical public services.”

By the following Friday, 13 days after the flood, Secretary Chertoff announced that operational responsibility for the Katrina response was shifting from FEMA to the Coast Guard, and that Coast Guard Vice Admiral Thad Allen would take charge. FEMA Director Brown resigned the following Monday.

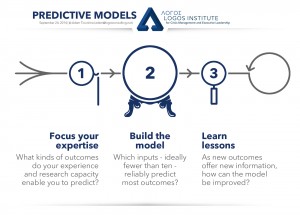

9 Lessons for Leaders and Communicators

The Katrina anniversary is an opportunity to reflect on foundational principles of effective crisis management. These include:

- Leaders are judged based on how they deal with their most difficult challenges. Crises can literally make or break reputations.

- Crisis management is the management of choices – the management of decisions that leaders make when things have the potential to go very wrong.

- There is a rigor to effective crisis management that is equivalent to the rigor found in other business processes. But that rigor is often unknown, ignored, or misapplied by many leaders, to their own and their organizations’ misfortune. That rigor includes a systematic way to think in a crisis.

- Every crisis is a business problem before it is a communication problem, and you cannot communicate your way out of a business problem. Crisis management is far more than skillful public relations. Effective crisis response consists of a carefully managed process that calibrates smart actions with smart communication: Crisis Response = Effective Action + Effective Communication.

- The key to making smart choices is to use the right decision criteria – the proper basis for choice. And that means asking the right question: What would reasonable people appropriately expect a responsible organization to do in this situation?

- Trust arises when stakeholders’ legitimate expectations are met. Trust falls when expectations are unmet.

- Framing decisions in light of stakeholder expectations leads to smarter choices faster, and maintains stakeholders’ trust.

- In a crisis, all stakeholders expect a responsible organization or leader to care. To care that something has happened; to care that people need help; to care that something needs to be done.

- The single biggest predictor of loss of trust and confidence, of loss of reputation, and of financial and operational harm, is the perception that the organization or leader do not care. Effective crisis response, at a minimum, begins with a timely demonstration of caring. And it continues with a persistent demonstration that the organization and leader continue to care, for as long as the expectation of caring exists.

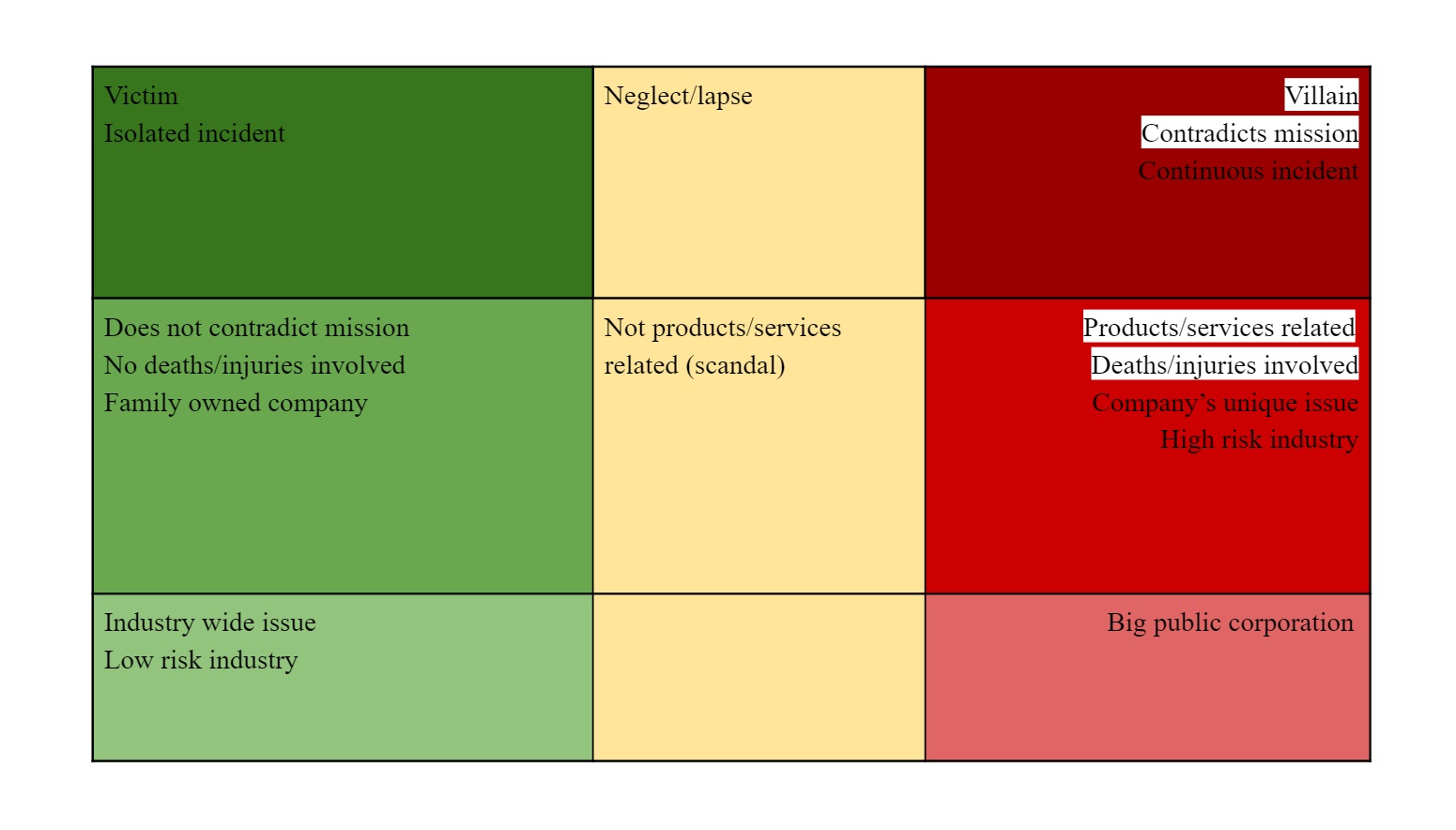

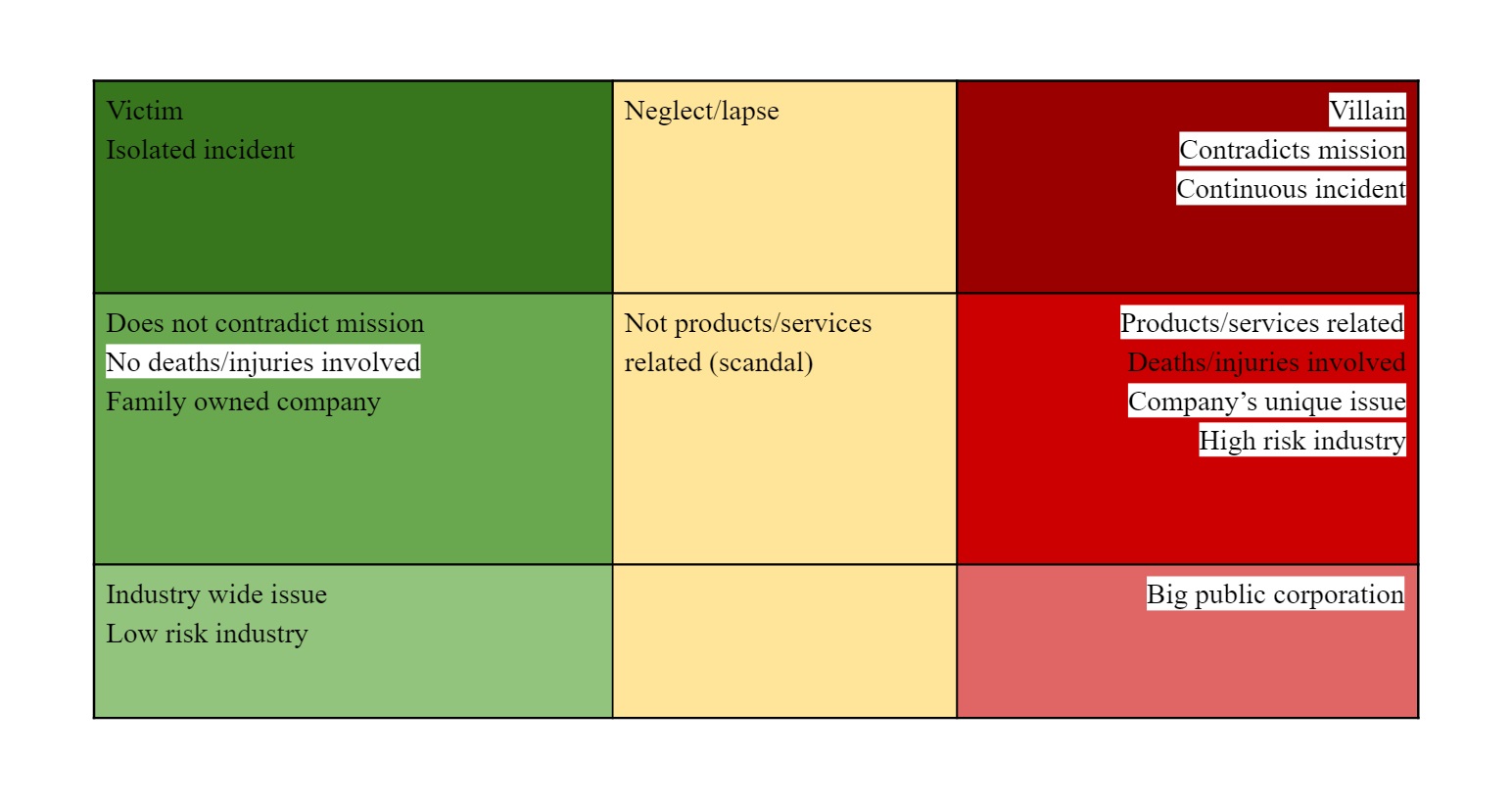

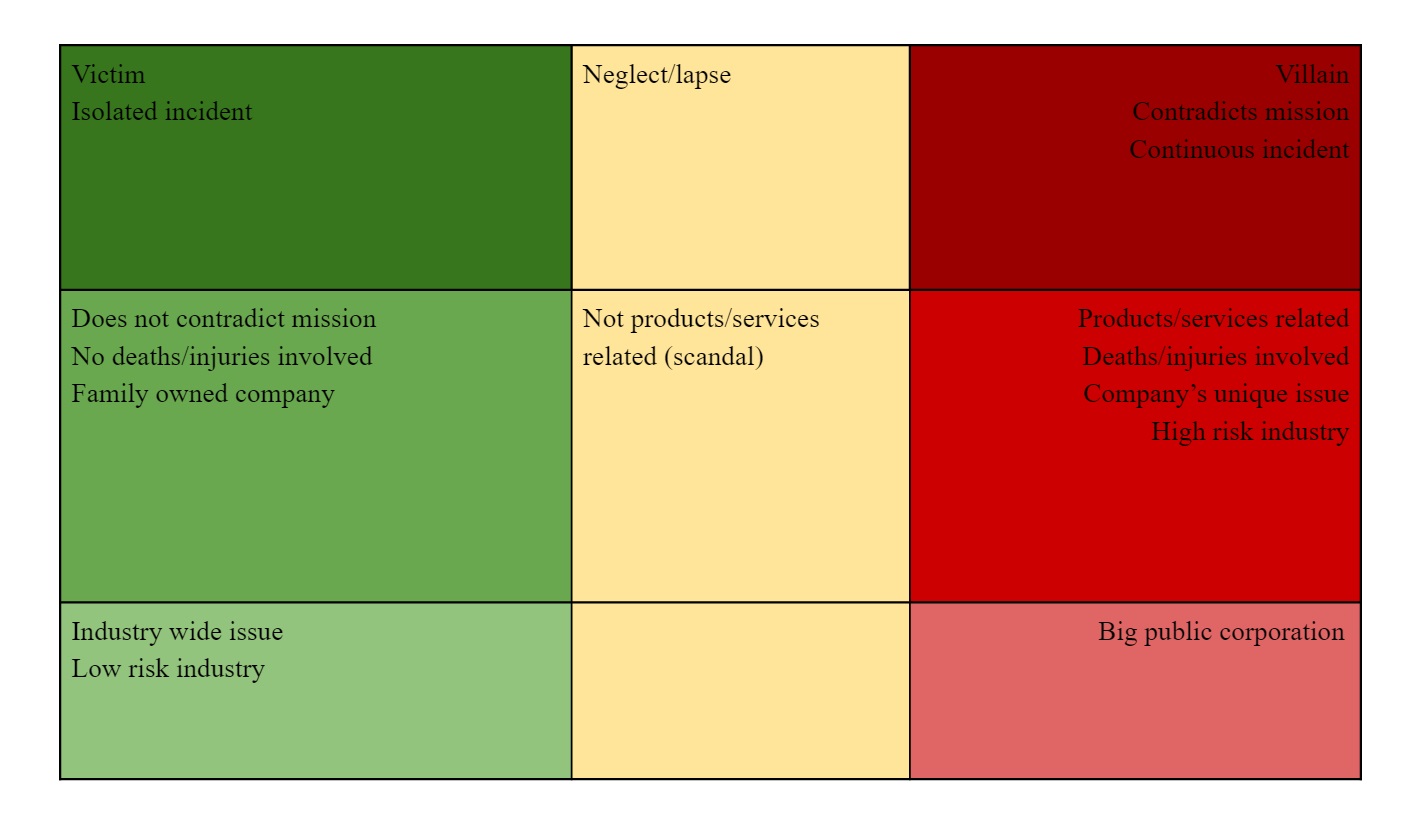

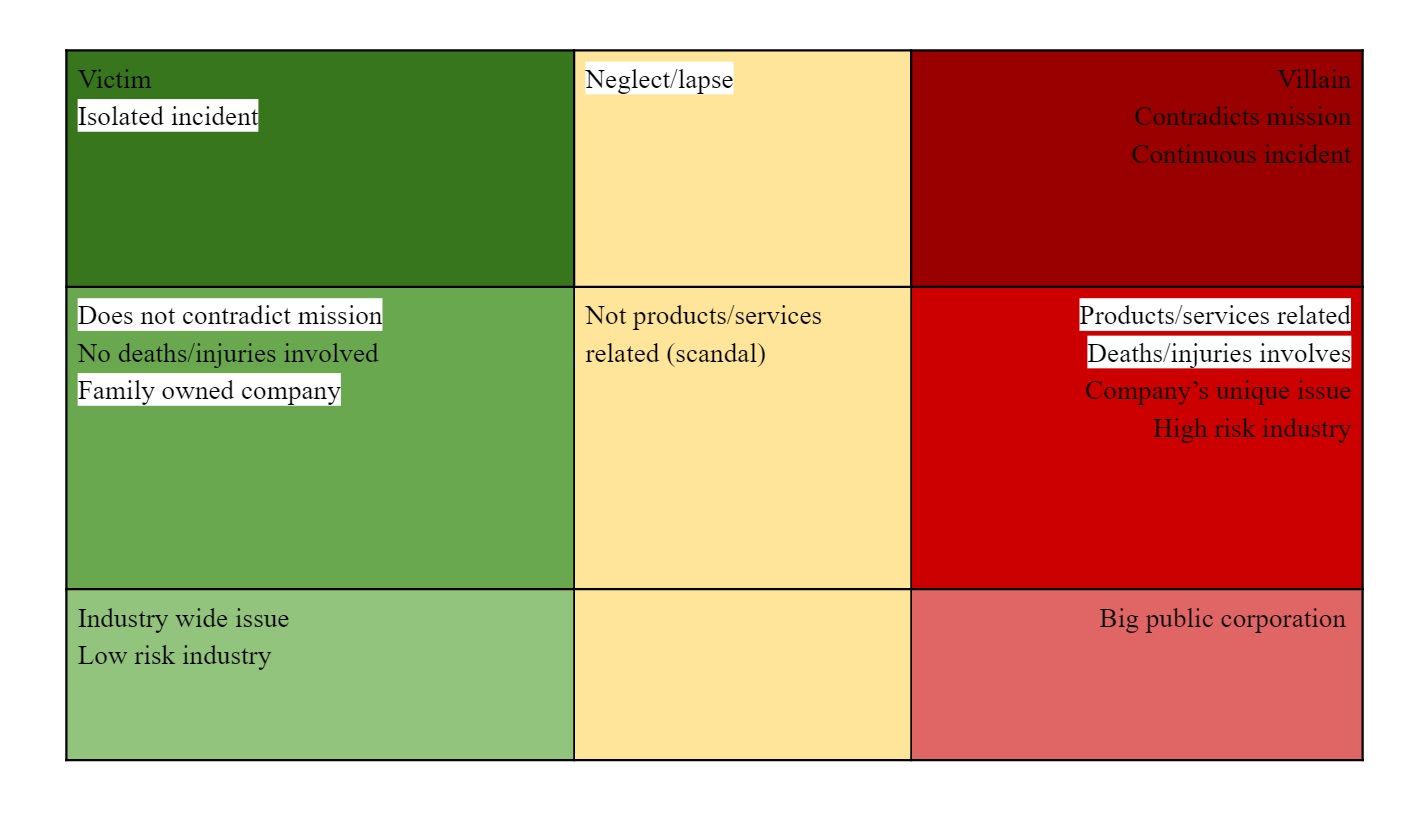

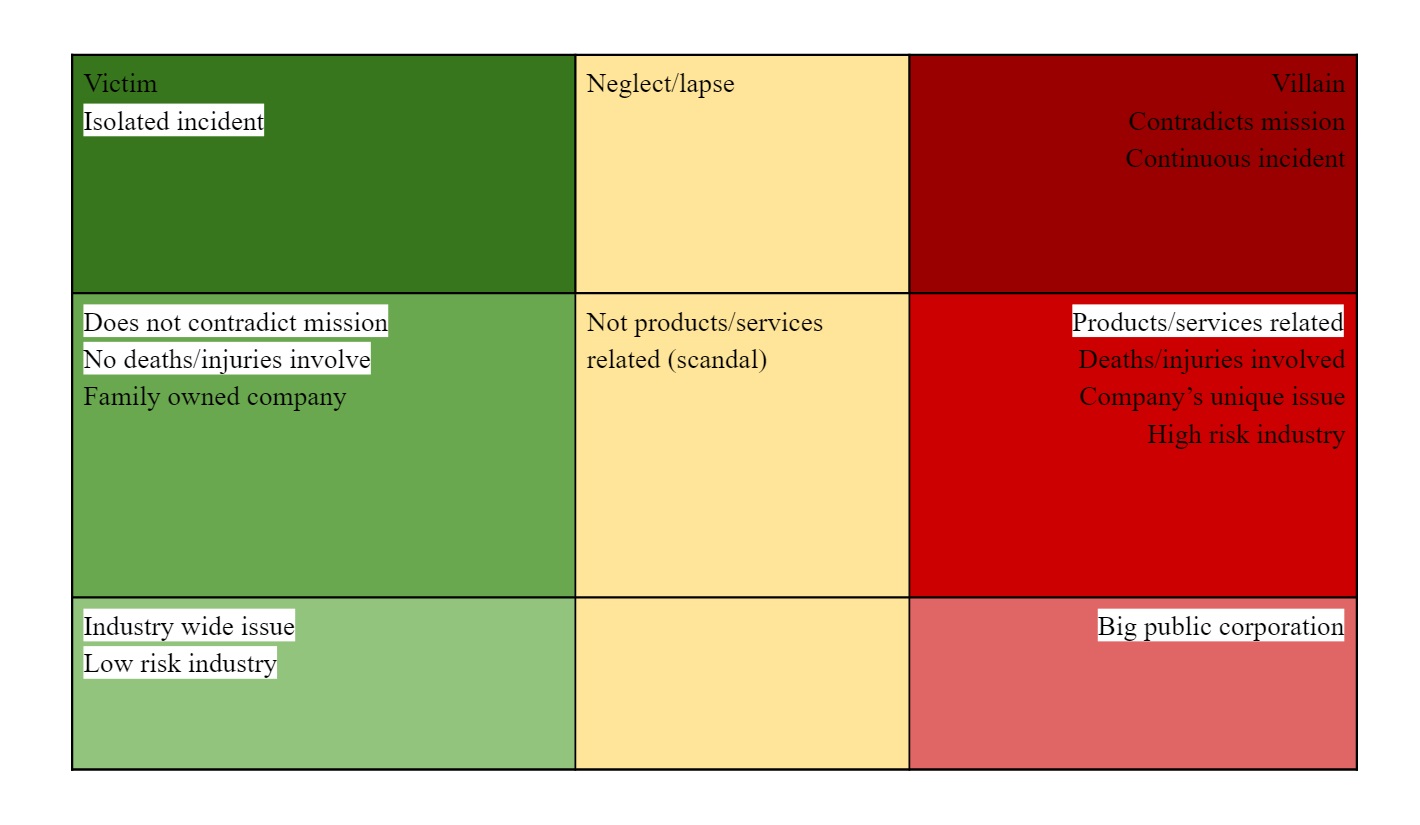

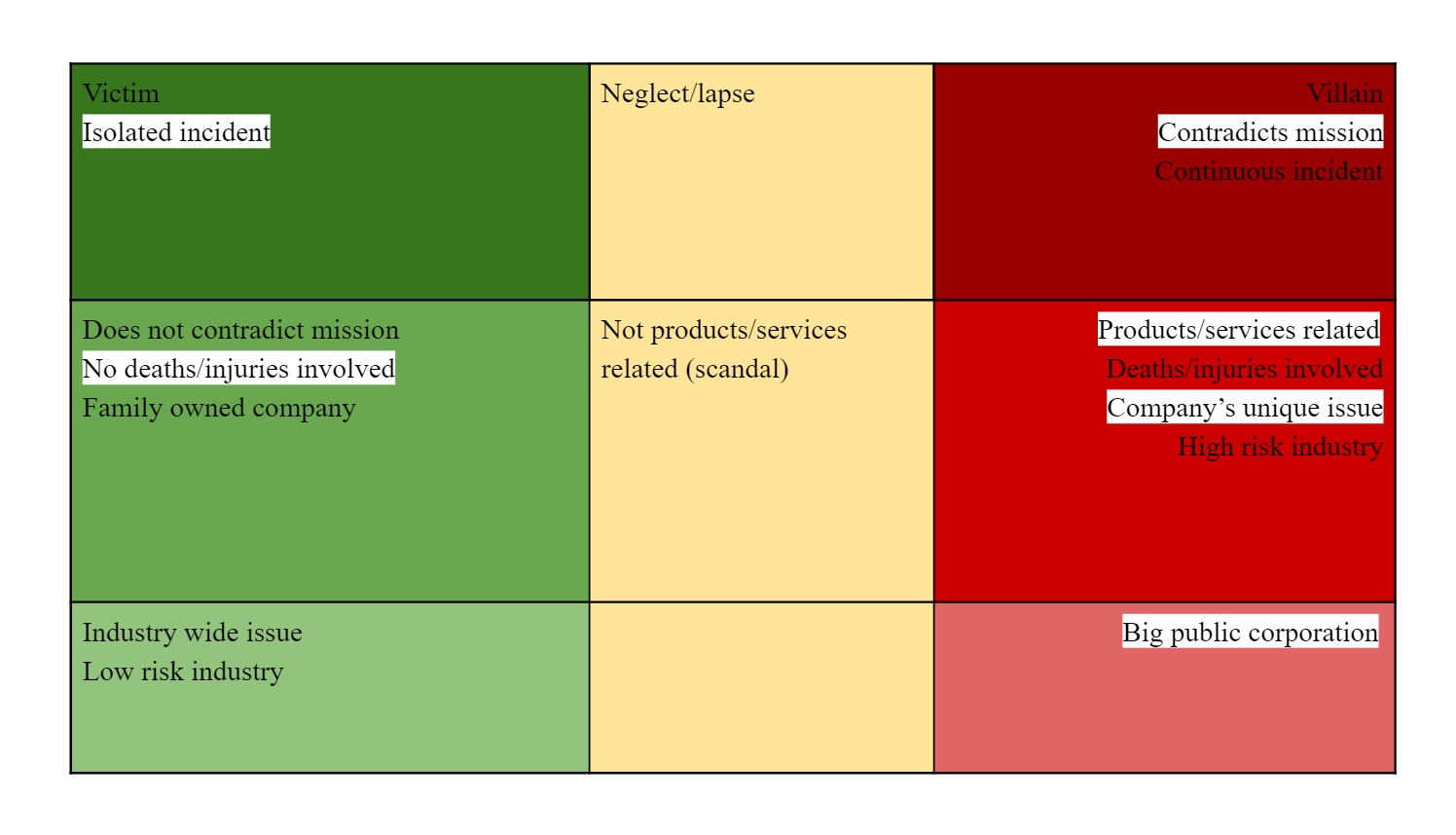

Brand loyalty is more likely to help a brand under conditions in the left column (green), and more likely to harm one under conditions in the right column (red).

Brand loyalty is more likely to help a brand under conditions in the left column (green), and more likely to harm one under conditions in the right column (red).

On January 31, 2012, the Susan G Komen Foundation announced its decision to stop funding Planned Parenthood.

On January 31, 2012, the Susan G Komen Foundation announced its decision to stop funding Planned Parenthood.